The Hall of Fame Running Back Room: Sorting Canton’s Best by What They Did Best

Part 1 of the Pro Football Hall of Fame Room Series

The Pro Football Hall of Fame doesn’t separate its players by skillset. It just puts a gold jacket on you and calls it a day. But what if we broke the Hall into rooms — not just by position, but by what made each player dangerous?

Welcome to the Running Back Room, where we’re sorting every HOF back into the archetype that defined their game. Not their stats. Not their era. Their identity.

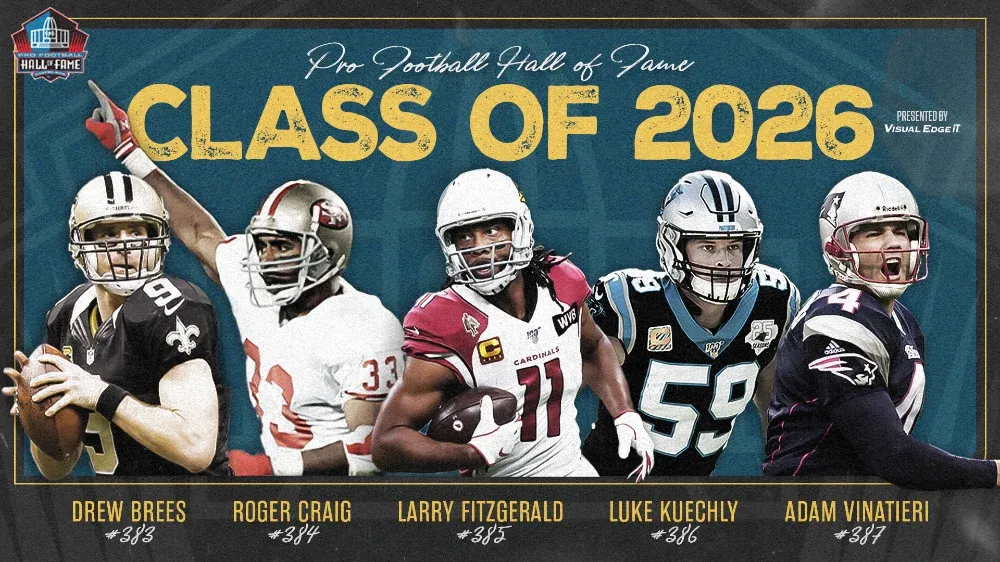

With Roger Craig’s long-overdue induction just announced as part of the Class of 2026, the running back wing of Canton just got a little more interesting — and a lot more versatile. Craig’s enshrinement is the perfect excuse to tear this room apart and rebuild it by skillset.

Here are the five archetypes we’re working with:

- The Bruiser — you knew it was coming, and you still couldn’t stop it

- The Game Breaker — one touch, and the whole stadium holds its breath

- The Elusive — ankles broken, defenders grabbing air

- The Dual Threat — just as lethal catching it as carrying it

- The Swiss Army Knife — blocking, receiving, running, short yardage — whatever the offense needed

But first — before we sort the room, we need to address the mountain.

The Mount Rushmore of Hall of Fame Running Backs

Four faces. Carved in stone. No take-backs. Here’s who belongs on the mountain — and if you’re already scrolling to the comments to yell at me, good. That means I did my job.

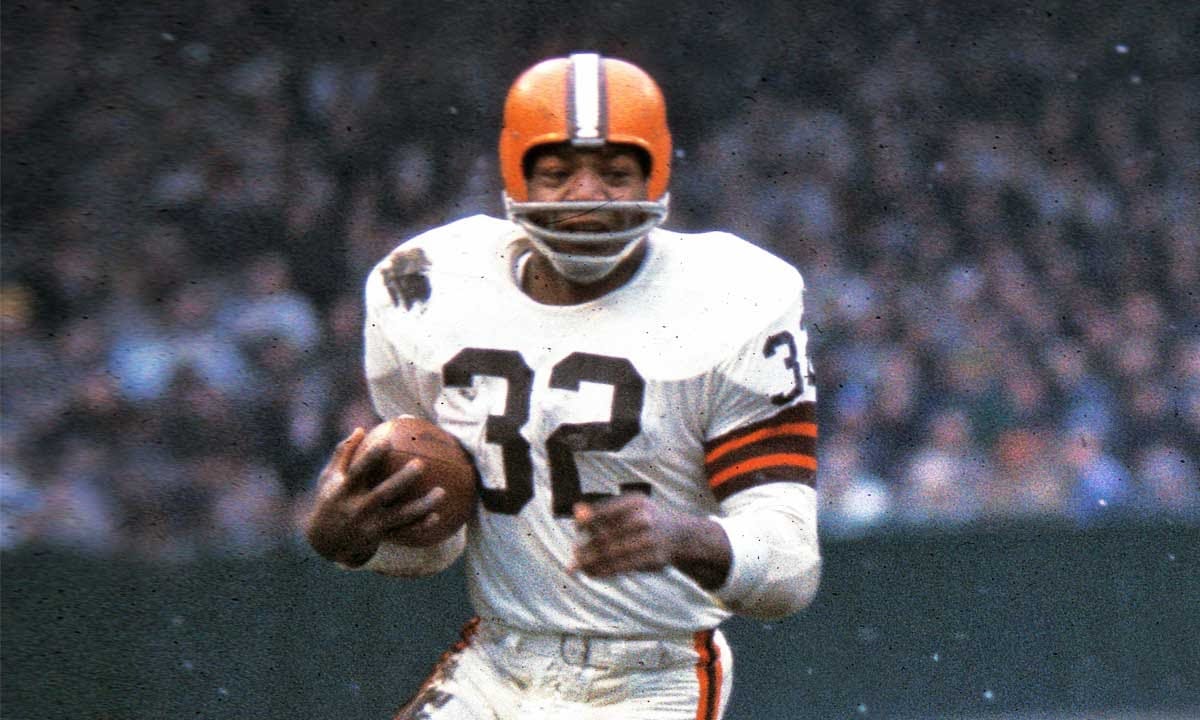

Jim Brown — Non-negotiable. Brown played nine seasons, led the league in rushing eight times, and retired as the greatest player anyone had ever seen. He didn’t decline. He didn’t fade. He just left. At 29. With nothing left to prove. Brown is the first face on the mountain because every running back who came after him is measured against what he did in a Cleveland Browns uniform. You don’t argue Jim Brown. You just nod.

Barry Sanders — The most breathtaking player to ever carry a football. Sanders played behind one of the worst offensive lines in football for a decade and still averaged 5.0 yards per carry, still won an MVP, still rushed for 2,053 yards in a single season, and still made every defender in the NFL look like they were running in sand. He retired at 30, 1,457 yards short of the all-time rushing record, because he was done watching the Lions waste his prime. That decision — walking away from immortal numbers because the situation wasn’t worth it — might be the most legendary thing any running back has ever done.

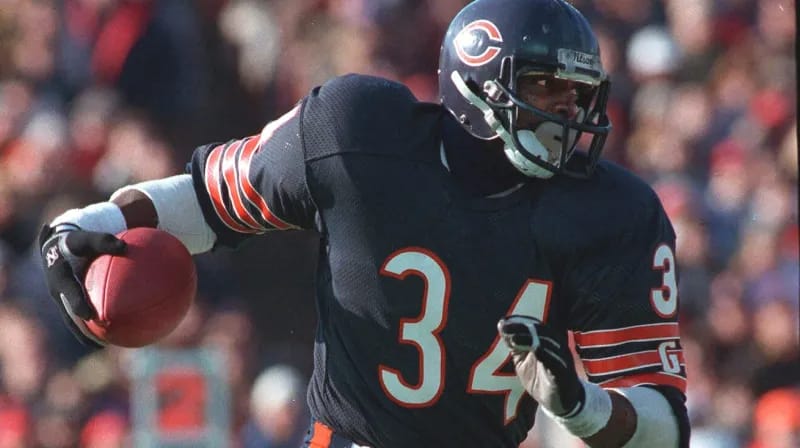

Walter Payton — Sweetness is the most complete running back who ever lived. Power. Elusiveness. Receiving. Blocking. Toughness. Payton held the all-time rushing record for nearly two decades and did it while carrying a Bears franchise that gave him almost no help for the first half of his career. He once rushed for 275 yards against the Vikings with the flu. He missed one game in 13 seasons. One. Payton didn’t just play running back — he defined what the position could be.

Eric Dickerson — And here’s where the hate mail starts. Dickerson owns the single-season rushing record — 2,105 yards in 1984 — and nobody has touched it in over 40 years. Adrian Peterson came within 8 yards. That’s it. That’s as close as anyone has gotten to what Dickerson did as a second-year player gliding through defenses in rec specs. He rushed for over 1,800 yards three times in his first four seasons. He had five First-Team All-Pro selections and four rushing titles. Dickerson’s peak was the highest peak any running back has ever reached, and the record that proves it is still standing on the wall, untouched, collecting dust, daring someone to come get it.

So where’s Emmitt Smith?

Yeah, we said it. The NFL’s all-time leading rusher — 18,355 yards, 164 rushing touchdowns, three Super Bowl rings — is not on this mountain. Go ahead, Cowboys fans. Get your fingers warmed up.

Here’s the thing: Emmitt Smith is a Hall of Famer. First ballot. No debate. But Rushmore isn’t the Hall of Fame. Rushmore is about transcendence — and Emmitt’s greatness was built on volume, longevity, and the greatest offensive line in NFL history. Troy Aikman. Michael Irvin. Larry Allen. Nate Newton. Erik Williams. That supporting cast was absurd.

The numbers tell the story. Emmitt’s career yards-per-carry? 4.2 — the lowest of any back on this mountain. His best single season — 1,773 yards — doesn’t crack the top 20 all-time. Meanwhile, Dickerson hit 2,105 behind a Rams offensive line that nobody remembers because Dickerson made them irrelevant. Emmitt needed the machine. Dickerson was the machine.

And before you throw rings at us: Barry Sanders won zero Super Bowls and Jim Brown won one NFL Championship. Rings are a team stat. Rushmore is about the individual.

Emmitt Smith is the greatest accumulator in NFL history. Eric Dickerson is the most dominant rusher. There’s a difference. And on this mountain, dominance wins.

Drop your Rushmore in the comments. We know you’ve got one.

Now let’s sort the room.

The Bruiser Room

These backs didn’t ask for a hole. They made one. The Bruiser archetype is defined by raw power, punishing contact, and a running style that turned linebackers into speed bumps. You didn’t want to tackle these guys. You had to.

Jim Brown (Cleveland Browns, 1957–1965) The prototype. Brown combined a lacrosse player’s athleticism with a freight train’s force. At 6’2”, 232 pounds, he was bigger than most linebackers he ran over. Nine seasons. Eight rushing titles. Zero signs of slowing down when he walked away. Brown didn’t break tackles — he punished defenders for attempting them. He’s the measuring stick for every back who ever laced up.

Earl Campbell (Houston Oilers/New Orleans Saints, 1978–1985) The Tyler Rose ran like he was personally offended by everyone wearing a different jersey. Campbell’s thighs were the size of tree trunks, and he used them to deliver punishment that shortened careers. Three consecutive rushing titles out of the gate. The 1979 Monday Night Football game against the Dolphins — 199 yards, four touchdowns — remains one of the most violent individual performances in NFL history.

Jerome Bettis (Los Angeles/St. Louis Rams, Pittsburgh Steelers, 1993–2005) The Bus didn’t do finesse. At 5’11”, 255 pounds, Bettis was a bowling ball with cleats. He’d run through your chest, step over you, and do it again on the next play. Six Pro Bowls, 13,662 career rushing yards, and a Super Bowl ring in his final game. Pittsburgh’s identity for a decade was basically “give the ball to Jerome and get out of the way.”

Larry Csonka (Miami Dolphins/New York Giants, 1968–1979) The centerpiece of the only undefeated season in NFL history. Csonka was the battering ram of those Dolphins teams — 6’3”, 235 pounds of fullback fury. He didn’t break long runs. He broke wills. His Super Bowl VIII performance — 145 yards, 2 touchdowns against the Vikings — was a masterclass in physical domination.

John Riggins (New York Jets/Washington Redskins, 1971–1985) The Diesel didn’t just run hard — he ran hard in the moments that mattered most. Riggins’ signature moment, the 43-yard touchdown run in Super Bowl XVII where he ran through Don McNeal, is one of the defining plays in championship history. At 33, he rushed for 24 touchdowns. Riggins was proof that power doesn’t expire — it just gets angrier.

Marion Motley (Cleveland Browns, 1946–1953) One of the first Black players in pro football’s modern era, and arguably the most physically dominant back of the 1940s and 50s. At 238 pounds, Motley was a wrecking ball who also happened to be an elite blocker. He averaged 5.7 yards per carry for his career — a number that still holds up against anyone, any era. Motley didn’t just break barriers. He ran through them.

Bronko Nagurski (Chicago Bears, 1930–1937, 1943) Before there were archetypes, there was Bronko. The legend goes that he once ran so hard he cracked a brick wall at Wrigley Field. Exaggeration? Probably. But the fact that people believed it tells you everything about how this man played football.

The Game Breaker Room

One cut. One burst. Goodbye. Game Breakers are the backs who could turn a 2-yard run into an 80-yard touchdown in a blink. They didn’t grind you down — they demoralized you with a single play.

Eric Dickerson (Los Angeles Rams/Indianapolis Colts/Los Angeles Raiders/Atlanta Falcons, 1983–1993) The single-season rushing record holder — 2,105 yards in 1984 — and the smoothest strider in NFL history. Dickerson’s upright running style and long speed made him look like he was gliding while everyone else was grinding. The goggles. The effortless burst. He made the hardest thing in football look easy.

O.J. Simpson (Buffalo Bills/San Francisco 49ers, 1969–1979) The Juice was the first player to break 2,000 yards in a season, doing it in only 14 games (a record that still stands — every other 2,000-yard back needed 16). Simpson’s combination of breakaway speed and vision was revolutionary for the early ’70s. His 1973 season — 2,003 yards — changed what people thought was possible for a running back.

Gale Sayers (Chicago Bears, 1965–1971) The Kansas Comet might have the highest peak of any running back ever, and he only played seven seasons (really five healthy ones). Six touchdowns in a single game as a rookie — in the mud at Wrigley Field. Sayers moved like a different species. His cuts were so sharp they looked choreographed. Injuries robbed us of what could have been the greatest career ever.

Tony Dorsett (Dallas Cowboys/Denver Broncos, 1977–1988) Dorsett holds the record for the longest run from scrimmage in NFL history — 99 yards against the Vikings on Monday Night Football in 1983. That play encapsulates everything about him: patience, explosion, and gone. He was the Cowboys’ offensive engine for a decade and finished with 12,739 career rushing yards.

Terrell Davis (Denver Broncos, 1995–2001) The shortest HOF career at the position, and nobody argues with it. Davis’ peak was a nuclear event: back-to-back Super Bowl wins, an MVP season (2,008 rushing yards in 1998), and a Super Bowl XXXII performance where he ran for 157 yards with a migraine so bad he could barely see. His postseason numbers — 1,140 yards and 12 touchdowns in 8 games — are absurd.

Ollie Matson (Chicago Cardinals/Los Angeles Rams/Detroit Lions/Philadelphia Eagles, 1952–1966) An Olympic sprinter (1952 Helsinki, bronze in the 400m and silver in the 4x400m relay) who brought world-class speed to professional football. Matson was so valuable that the Rams traded nine players to get him. His all-purpose ability was ahead of its time, and his speed on the edge was simply unfair for the era.

Hugh McElhenny (San Francisco 49ers/Minnesota Vikings/New York Giants/Detroit Lions, 1952–1964) The King made the 49ers’ offense go in the 1950s. McElhenny’s open-field running was electric — he combined speed, elusiveness, and an almost improvisational style that made him impossible to gameplan against. Before the West Coast offense made San Francisco famous, McElhenny was putting on a show at Kezar Stadium.

The Elusive Room

These backs didn’t beat you with power or speed alone — they beat you with movement. Elusiveness is about making defenders miss in phone booths, turning nothing into something, and making the first man wrong every single time.

Barry Sanders (Detroit Lions, 1989–1998) The greatest open-field runner in the history of the sport. Period. Sanders made defenders look foolish on a nightly basis behind one of the worst offensive lines in football. He lost yards on more plays than any other great back because he had to create everything himself — and he still averaged 5.0 yards per carry for his career. His 1997 MVP season — 2,053 yards — was a highlight reel from start to finish. Sanders retired at 30, walking away 1,457 yards short of the all-time rushing record. We’re still not over it.

Walter Payton (Chicago Bears, 1975–1987) Sweetness could do everything — and elusiveness was at the core. Payton’s jump cuts, stiff arms, and ability to make the first defender miss were legendary. But unlike pure finesse backs, he could also lower his shoulder and put a linebacker on his back. The all-time rushing record holder when he retired (16,726 yards), Payton was the most complete runner of his generation. He belongs in multiple rooms, but his ability to make you miss in space earns him the Elusive tag.

Marcus Allen (Los Angeles Raiders/Kansas City Chiefs, 1982–1997) Allen’s Super Bowl XVIII run — that reverse-field, 74-yard touchdown against Washington — might be the single greatest run in Super Bowl history. Allen’s vision and patience allowed him to set up defenders and then leave them grasping at air. A Heisman winner, Super Bowl MVP, and NFL MVP, Allen’s ability to change direction without losing speed was his signature weapon.

Curtis Martin (New England Patriots/New York Jets, 1995–2005) Martin wasn’t flashy. He was surgical. His elusiveness was subtle — a slight hesitation, a gentle cut, and suddenly the linebacker who had an angle was reaching for nothing. Martin rushed for over 1,000 yards in 10 of his 11 seasons and won a rushing title at age 31. He made the craft of running back look like an art form.

Emmitt Smith (Dallas Cowboys/Arizona Cardinals, 1990–2004) The all-time leading rusher in NFL history (18,355 yards) doesn’t get enough credit for his elusiveness. Smith wasn’t the fastest or the most powerful, but his ability to set up blocks, make subtle cuts, and avoid the big hit allowed him to play 15 seasons at an elite level. His vision was a form of elusiveness — he saw the miss before the defender even committed.

Floyd Little (Denver Broncos, 1967–1975) Little was the Broncos before the Broncos were anything. Playing on consistently bad teams, Little’s elusiveness and toughness made him the entire offense. He could make you miss in the hole or in the open field, and he carried the franchise on his back during its lean years. The city of Denver literally kept its NFL team because of Floyd Little — the fans wouldn’t let the Broncos move because they loved watching him play.

The Dual Threat Room

These backs were just as dangerous catching the ball as carrying it. The Dual Threat archetype redefined what a running back could be — a weapon in the passing game who forced defensive coordinators to account for them on every snap.

Marshall Faulk (Indianapolis Colts/St. Louis Rams, 1994–2005) The most complete offensive weapon of the modern era. Faulk’s 1999–2001 run with the Greatest Show on Turf was ridiculous: 26 total touchdowns in 2000, 2,429 yards from scrimmage. He was equally comfortable running between the tackles, catching screens, or lining up in the slot. Faulk forced defenses to choose their death — stop the run and he’d beat you through the air, take away the pass and he’d gash you on the ground.

Roger Craig (San Francisco 49ers/Los Angeles Raiders/Minnesota Vikings, 1983–1993) The newest Hall of Famer, and the OG dual threat. Craig became the first player in NFL history to record 1,000 rushing yards and 1,000 receiving yards in the same season (1985). He was Bill Walsh’s Swiss Army knife in the West Coast offense, a back who could run routes like a receiver and still carry the ball 200+ times. Three Super Bowl rings, and the template for every dual-threat back who followed. Craig waited 28 years for this jacket. The wait is over — and the archetype he pioneered is now the standard.

Lenny Moore (Baltimore Colts, 1956–1967) Before anyone was using the term “dual threat,” Moore was living it. He played both halfback and flanker — essentially a running back/wide receiver hybrid decades before it became fashionable. Moore scored touchdowns in 18 consecutive games, an NFL record that stood for decades. He was Johnny Unitas’ secret weapon: line him up anywhere and let the defense guess wrong.

LaDainian Tomlinson (San Diego Chargers/New York Jets, 2001–2011) LT was the total package: 28 touchdowns in 2006 (then an NFL record), elite receiving ability, and he could even throw the ball (7 career TD passes). Tomlinson combined vision, hands, and football IQ into one of the most productive careers ever. He made the Chargers relevant for an entire decade and did it all without ever winning the big one — a fact that somehow makes his individual greatness even more impressive.

Frank Gifford (New York Giants, 1952–1960, 1962–1964) Before he was a broadcaster, Gifford was one of the most versatile offensive weapons in NFL history. He played halfback, wide receiver, and defensive back during his career. As a runner, he had soft hands and the ability to beat you as a receiver out of the backfield. Gifford helped define what a modern offensive weapon could look like.

Charley Taylor (Washington Redskins, 1964–1977) (Listed as WR by HOF, but began career as RB) Taylor started his career as a running back before switching to wide receiver — and starred at both. His ability to do both at a high level makes him the ultimate dual-threat argument. He retired as the NFL’s all-time leading receiver.

The Swiss Army Knife Room

These backs did whatever you needed, whenever you needed it. Blocking. Short yardage. Receiving. Special teams. The Swiss Army Knife archetype is about versatility beyond just running and catching — these guys were football players in the truest sense.

Franco Harris (Pittsburgh Steelers/Seattle Seahawks, 1972–1984) Harris could run between the tackles, catch passes, block for Bradshaw, and deliver in the biggest moments. The Immaculate Reception is the most famous play in NFL history, but Harris’ real value was his consistency: 12,120 career rushing yards, four Super Bowl rings, and the ability to do whatever the Steelers needed on any given play. Harris was never the best at any single thing — but he was excellent at everything.

Thurman Thomas (Buffalo Bills/Miami Dolphins, 1988–2000) Thomas was the engine of those four consecutive Super Bowl Bills teams. He could run inside, run outside, catch passes, and pick up blitzes. His 1991 MVP season — 2,038 yards from scrimmage — showcased a player who was the entire offense. Thomas’ versatility was what made Buffalo’s no-huddle attack so dangerous: he could line up anywhere and do anything.

Paul Hornung (Green Bay Packers, 1957–1962, 1964–1966) The Golden Boy was a halfback, placekicker, and all-around weapon in Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay dynasty. In 1960, Hornung scored 176 points — a single-season record that stood for 46 years. He could run, catch, kick, and even throw. Hornung is the definition of “whatever the team needs.”

Joe Perry (San Francisco 49ers/Baltimore Colts, 1948–1963) The Jet was the first player in NFL history to rush for 1,000 yards in consecutive seasons. A fullback who could do it all — run with power, catch passes, and block — Perry was essential to the 49ers’ Million Dollar Backfield. His blocking was as valuable as his rushing, making him the prototype Swiss Army Knife back.

Leroy Kelly (Cleveland Browns, 1964–1973) Imagine replacing Jim Brown. Now imagine doing it successfully. Kelly stepped into the biggest shoes in football and delivered — three rushing titles, six Pro Bowls, and a complete skillset that included running, receiving, and returning kicks. Kelly wasn’t a specialist. He was a football player.

Edgerrin James (Indianapolis Colts/Arizona Cardinals/Seattle Seahawks, 1999–2009) Edge was a workhorse who could do everything. Run between the tackles? Yes. Catch passes from Peyton Manning? Absolutely. Pick up the blitz? Without hesitation. James led the league in rushing twice, ran for 12,246 career yards, and was one of the most reliable backs of his era. He did everything well, nothing flashy, and was exactly what his teams needed him to be.

Doak Walker (Detroit Lions, 1950–1955) Walker was a halfback, kicker, punt returner, and kick returner — a true jack-of-all-trades in an era when versatility was born of necessity. He won two NFL championships and was named to four Pro Bowls in a career cut short at just six seasons.

The Hybrids: Players Who Defy One Room

Here’s where the debate gets spicy. Some of these Hall of Famers don’t fit neatly into one archetype — and that’s what makes this fun.

Walter Payton — Listed as Elusive, but was also a devastating blocker, a willing receiver, and ran the ball with power that would qualify him as a Bruiser. Sweetness is legitimately a three-room player.

Jim Brown — The ultimate Bruiser, but he also had breakaway speed (Game Breaker) and nimble feet that let him make defenders miss (Elusive). Brown might belong in every room.

Barry Sanders — Pure Elusive, but his ability to turn nothing into a 50-yard touchdown gives him Game Breaker credentials too.

Marshall Faulk — The purest Dual Threat, but his versatility (blocking, situational awareness) makes a Swiss Army Knife case too.

LaDainian Tomlinson — Dual Threat for sure, but his 28-TD season and ability to throw the ball also give him Swiss Army Knife energy.

Marcus Allen — Listed as Elusive, but his patience and receiving ability make a Dual Threat argument. His Super Bowl XVIII performance? Pure Game Breaker.

Who’s Missing? The HOF Running Back Snubs

The Hall of Fame has some glaring omissions at running back. These are the guys who should be in the building but are still waiting outside:

Frank Gore — Third all-time in career rushing yards (16,000). Sixteen seasons. Nine 1,000-yard campaigns. Gore was a first-year eligible finalist in 2026 and didn’t get in, with Roger Craig taking the running back slot. His longevity is historically elite, and the “Hall of Very Good” argument doesn’t hold up when you’re third on the all-time list. Archetype: Swiss Army Knife.

Marshawn Lynch — Beast Mode was a cultural phenomenon and a genuinely great running back. 10,413 career rushing yards, 85 rushing touchdowns, and a Super Bowl ring with the Seahawks. The Beast Quake run against the Saints might be the most iconic run of the 21st century. His candidacy will test whether the Hall values peak dominance or career longevity. Archetype: Bruiser.

Shaun Alexander — NFL MVP in 2005 (27 rushing touchdowns, then a record). Alexander’s peak was absurd, but his falloff was steep. The “short window of greatness” debate will define his candidacy. Archetype: Game Breaker.

Edgerrin James — Wait, he’s already in. Just making sure you’re paying attention. But seriously, it took Edge until 2023 to get his jacket. The backlog at running back is real.

Tiki Barber — 10,449 rushing yards, 2,217 receiving yards, and one of the most productive stretches in NFL history from 2004–2006. Barber’s candidacy is complicated by his early retirement and post-career controversies. Archetype: Dual Threat.

Corey Dillon — 11,241 career rushing yards and a key piece of New England’s 2004 Super Bowl team. Dillon was a bruising, between-the-tackles runner who dominated in Cincinnati before finding championship success. Archetype: Bruiser.

Future Entrants: The Next Gold Jackets

These active or recently retired players are building — or have built — Hall of Fame cases:

Adrian Peterson — First-year eligible in 2027, and a near-lock for induction. The last non-QB MVP (2012, 2,097 rushing yards), three-time rushing champion, and the fifth-leading rusher in NFL history. Peterson’s on-field resume is unimpeachable: seven Pro Bowls, four First-Team All-Pro selections, and a 2012 season that was one of the greatest individual campaigns in history. Off-field issues (a 2014 child abuse case and a 2025 arrest) could slow his candidacy, but the talent was undeniable. Archetype: Bruiser/Game Breaker hybrid.

Derrick Henry — Still active and still punishing. Henry’s combination of size (6’3”, 247 pounds) and speed is unlike anything the position has ever seen. His 2,000-yard 2020 season and his 2024 playoff run with the Ravens have built a resume that’s getting harder to ignore. If he keeps stacking seasons, Henry enters the Bruiser Room as its modern king. Archetype: Bruiser.

Christian McCaffrey — The modern Roger Craig. McCaffrey became just the third player ever to post 1,000 rushing and 1,000 receiving yards in the same season (2019), joining Craig and Marshall Faulk. Injuries have been a factor, but when healthy, CMC is the most versatile offensive weapon in football. He needs sustained health and longevity to build a Canton case, but the talent and archetype mastery are already there. Archetype: Dual Threat/Swiss Army Knife.

Nick Chubb — The most efficient power runner of his generation when healthy. Chubb’s 5.3 career yards per carry and his ability to break tackles at a historic rate put him in Bruiser territory, but a devastating 2023 knee injury creates a major “what if.” If Chubb returns to form and stacks more elite seasons, the case builds. Archetype: Bruiser.

Saquon Barkley — The most talented back of his generation, Barkley’s 2024 season with the Eagles — 2,005 rushing yards and a Super Bowl appearance — has reignited his HOF trajectory after years of injuries derailed his Giants tenure. At his best, Barkley is a Game Breaker with Dual Threat versatility. The question is whether he can sustain it. Archetype: Game Breaker/Dual Threat.

The Final Sort

Archetype: Hall of Famers

Bruiser

Jim Brown, Earl Campbell, Jerome Bettis, Larry Csonka, John Riggins, Marion Motley, Bronko Nagurski

Game Breaker

Eric Dickerson, O.J. Simpson, Gale Sayers, Tony Dorsett, Terrell Davis, Ollie Matson, Hugh McElhenny

Elusive

Barry Sanders, Walter Payton, Marcus Allen, Curtis Martin, Emmitt Smith, Floyd Little

Dual Threat

Marshall Faulk, Roger Craig, Lenny Moore, LaDainian Tomlinson, Frank Gifford, Charley Taylor

Swiss Army Knife

Franco Harris, Thurman Thomas, Paul Hornung, Joe Perry, Leroy Kelly, Edgerrin James, Doak Walker

Agree? Disagree? Is Emmitt Smith getting robbed on this Rushmore? Is LT more deserving than Dickerson? Think Barry Sanders is a Game Breaker, not Elusive? Drop your Rushmore and your room assignments in the comments. Cowboys fans — we’re waiting.

Next up in the Hall of Fame Room Series: The Wide Receiver Room — where we break down the difference between a route technician, a deep threat, a possession receiver, and a YAC monster.

AfroPulse | Part 1 of 5 in the Pro Football Hall of Fame Room Series